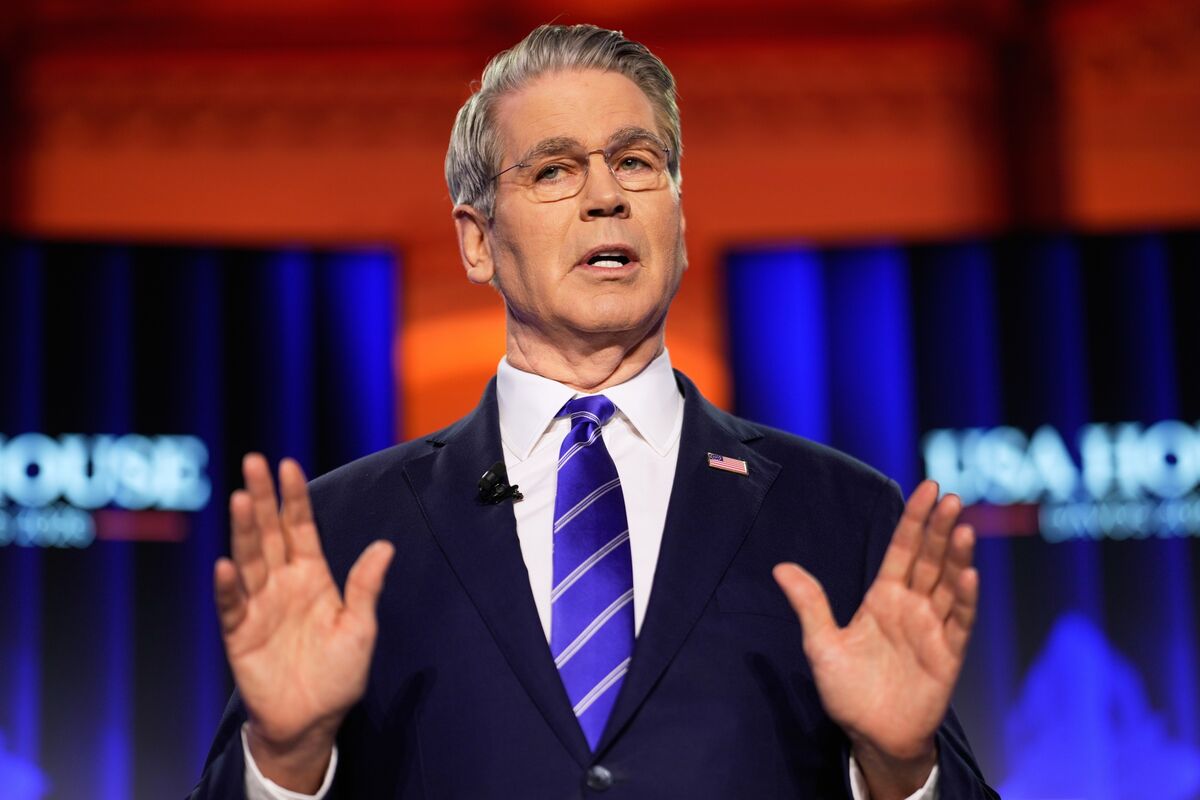

ANGELA WEISS / AFP via Getty Images

- “Stock Market Maestros” offers detailed investing advice from top fund managers.

- Experts share details of their processes, such as rebalancing and knowing when to exit a position.

- Some shared thoughts on popular tools like stop-losses

There are some investing tips that you hear over and over, but are light on specifics.

Diversify your portfolio. Don’t let emotion — whether it be fear or greed — guide your decisions. Invest early and often to take advantage of compounding.

But a new book of interviews with top investors from around the world features plenty of nuggets of advice that extend beyond the run-of-the-mill guidance.

In “Stock Market Maestros,” Lee Freeman-Shor, a former fund manager himself, and Clare Flynn Levy dig into the philosophy of 11 top money managers and break down their top takeaways in digestible bites.

Below, we’ve compiled six of the best nuggets of wisdom.

Keep an investing journal

You might check your portfolio every day, but do you write about it? Doing so can be helpful, especially for remembering why you’ve invested in something in the first place.

Maneesh Bajaj, a portfolio manager at Brown Advisory, said he can sometimes correct flaws in his investment process by looking back at his.

“I write down the rationale for every trade I place,” Bajaj said. “Where there are lessons to be learned from looking at my decisions in aggregate, I will incorporate those into the process.

Bajaj added that keeping track can help him realize when to be more decisive with a trade, informing him when it’s better to exit a losing investment.

Don’t necessarily think stop-losses are helpful

For the average investor who can’t watch markets all day long, stop-losses — which help you automatically get out of a position if it falls by a set percentage — are crucial tools for protecting capital.

But John Lin, the CIO of emerging markets value and China equities at Alliance Bernstein, said stop-losses are arbitrary and therefore potentially counterproductive if an investment thesis is still good.

“I don’t use stop losses because they are too formulaic. What makes 20% or 40% the right number to cut your losses?” Lin said. “I know when I should throw in the towel, but it is based on other factors. And when I decide to get out, I cut the whole thing. In my experience, selling in stages usually means you bleed performance along the way.”

John Barr, the portfolio manager of the Needham Aggressive Growth Fund, agreed, saying his best-ever investments would have been cut short by stop losses.

“Stop losses would be a disaster for me because they would have stopped out every one of my top 20 biggest winners. The average drawdown of my 20 biggest winners during the time I have held them has been 60—70%,” Barr said. “And they can be down and out for a year or longer. I wouldn’t know where to place the stop loss level. And if I used them, and they got triggered, I probably wouldn’t have bought in again after I had sold.”

Know when to rebalance

Say you invested in Nvidia in 2020. Your portfolio would be sitting pretty right now, and would probably have a heavy bias toward the stock given the 1,165% gain over the last five years.

But with the stock looking less invincible recently, it’s a good idea to try and understand when to lock in some of those gains and pare down your position. But how to do that?

One strategy is to sell at least the amount of your original position to ensure you can’t lose, or sell a set percentage, like half, of your position as it reaches different return milestones.

Dirk Enderlein, a portfolio manager at Wellington Management, and James Hanbury, the head of strategy at Lancaster Investment Management, say to think of it this way: If you were to open a position in a particular stock today, what’s the weighting in your portfolio you would give it?

“I don’t believe in letting a position grow and grow. You run the risk of falling in love with the idea, and when it goes against you, you don’t want to bring the weight down. This is what ends investment careers,” Enderlein said.

“I would argue that someone who let the position grow to 6% would not start the position at 6% if they were starting afresh,” he added.

Use the “Boiling Frog” screen to help know when to dump a position

It can be hard to know when to get out of a losing stock. Gorm Thomassen, the CIO of AKO Capital, likes to use something he’s dubbed the “Boiling Frog” screen — it alerts him to small but negative changes occurring that he should be aware of before it becomes too late.

For example, warning signs would appear when a company’s financial health appears to weaken, when a similar company warns its profits or earnings are set to take a hit, or when levels of insider selling spike.

Thomassen said he looks at the screen once a month.

Have a “farm team” of stocks

Andrew Hall, a fund manager at Invesco, said he sends some of his stocks back down to his “farm team” when they get too expensive. It’s a reference to minor league baseball, where players go to develop or rehab before heading to the Majors, and in Hall’s case it means reducing the stocks to small positions.

“I only do that if I think the chance of monetising it in the future is higher than if I were to exit,” he said. “Perhaps it would be better to sell and watch it on the bench. But the reality is nothing focuses the mind like having an ownership stake. And the size is small enough that if I get it wrong it does not really affect performance.”

Come up with specific safeguards to manage emotions

Hall, the Invesco fund manager, said he uses several methods for taking emotion out of his decision-making process.

One is that he waits until the evening before making a choice on an investment because it gives his emotions time to dissipate. He also goes on runs to think out a given investment decision he has to make. And when he finally does buy, he puts his position to work over the course of multiple days to ensure he still likes his thesis.

“For example I will buy 10 basis points a day for five days instead of buying 50 basis points on one day,” he said. “This is a way of lowering the emotional impact of the decision. And it gives me the opportunity to stop buying if it becomes clear that it was the wrong thing to do.”