Wall Street’s bull market looks to be galloping higher on borrowed time.

It’s been quite a phenomenal two years for investors. Since bottoming out in October 2022, the iconic Dow Jones Industrial Average (^DJI 0.42%), broad-based S&P 500 (^GSPC 0.56%), and innovation-driven Nasdaq Composite (^IXIC 0.83%) have all soared to multiple record-closing highs.

The stock market’s epic rally is being fueled by the rise of artificial intelligence (AI), excitement following President-elect Donald Trump’s victory, and corporate earnings growth widely surpassing consensus expectations.

While seemingly nothing looks to be standing in the way of these three catalysts, history isn’t as forgiving.

Image source: Getty Images.

The S&P 500 has reached uncharted territory

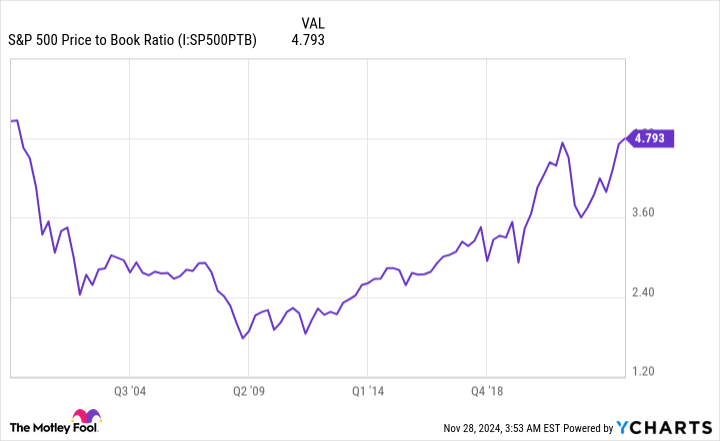

Over the last year, there has been no shortage of economic data points or forecasting tools that have warned of potential trouble for the U.S. economy and/or Wall Street. Examples include the first notable decline in U.S. money supply since the Great Depression, the longest yield-curve inversion on record, and a record high for the “Buffett Indicator.” However, there’s a new concern to add to the list: the benchmark S&P 500’s price-to-book (P/B) ratio.

For individual companies, their book value effectively shows what shareholders would receive if a company were, hypothetically, liquidated (i.e., its assets minus liabilities). While book value isn’t quite the imperative fundamental metric it once was, it still serves an important function in helping value investors identify undervalued stocks.

However, book value isn’t just a metric used for individual businesses. We can examine the collective book value of the companies that comprise major indexes to determine if the components, as a whole, are collectively cheap or pricey.

Over the last 25 years, the S&P 500’s P/B value has averaged 2.83, which isn’t particularly low, nor is it egregiously high. With the internet democratizing access to information in the mid-1990s and interest rates tumbling following the financial crisis, investors have been encouraged to take on more risk and invest in growth stocks, which would be expected to lead higher P/B ratios.

But there’s an undeniable threshold the S&P 500 has crossed that’s eventually (key word!) led to trouble every single time.

S&P 500 Price to Book Ratio data by YCharts. Readings are tabulated quarterly, with the latest reading (4.793) for the chart above from Sept. 30, 2024.

Prior to 2024, there had only been two instances in a quarter of a century when the S&P 500’s P/B ratio surpassed 4 during a bull market rally:

- The end of the fourth quarter of 2021 when the P/B ratio ended at 4.73.

- The end of the first quarter of 2000 when it hit what had been its record high of 5.06.

As of the closing bell on Nov. 26, 2024, the S&P 500’s P/B ratio stood at an all-time high of 5.30.

Following 2021’s Q4, the Dow, S&P 500, and Nasdaq Composite all spiraled into a bear market, with the S&P 500 losing around a quarter of its value. Meanwhile, the broad-based index shed 49% of its value when the dot-com bubble burst, with the Nasdaq Composite losing 78% on a peak-to-trough basis.

History is quite clear that once the S&P 500’s P/B ratio becomes extended, it’s simply a matter of time before a sizable correction occurs.

This isn’t the only valuation metric sounding alarm bells

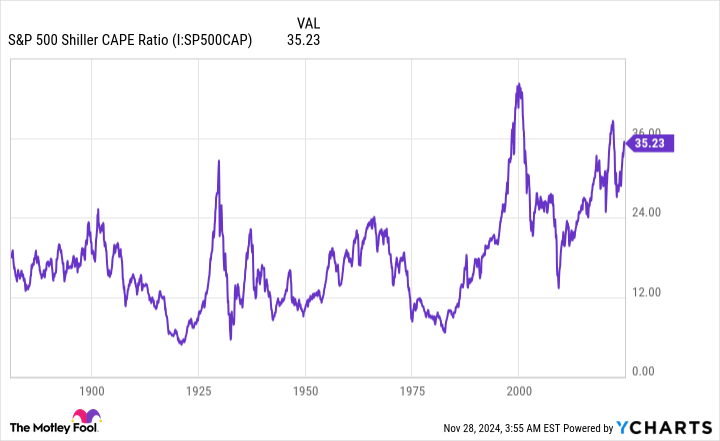

However, the S&P 500 breaching a never-before-seen price-to-book threshold isn’t the only valuation metric that’s raising eyebrows on Wall Street.

Most investors are probably familiar with the traditional price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio as a way to make quick evaluations of whether or not a stock is inexpensive or pricey. The P/E ratio divides a company’s (or index’s) share price into its trailing-12-month earnings per share (EPS) to make this assessment.

The potential problem with the traditional P/E ratio is that shock events render it useless. For instance, early-stage lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic ravaged corporate earnings for a short period and skewed the trailing-12-month EPS for most public companies.

S&P 500 Shiller CAPE Ratio data by YCharts.

What’s, arguably, a far more complete measure of value is the S&P 500’s Shiller P/E ratio, which is also referred to as the cyclically adjusted P/E ratio (CAPE ratio). The Shiller P/E is based on average inflation-adjusted EPS from the prior 10 years, which means it’s able to smooth out the lumpiness associated with short-term shock events.

When back-tested to 1871, the Shiller P/E has averaged a rather modest reading of 17.17. But you’ll note that this ratio has spent much of the last 30 years above this 153-year average, which is, once again, a reflection of the democratization of information, ease of access to online trading/investing, and lower prevailing interest rates.

But when the closing bell tolled on Nov. 26, the Shiller P/E stood at 38.41, which is its highest reading during the current bull market rally as well as the third-highest reading during a continuous bull market over the last 153 years. The only two times the S&P 500’s Shiller P/E ratio has been higher are (drum roll) prior to the dot-com bubble bursting when it hit an all-time high of 44.19, and immediately before the 2022 bear market when it briefly surpassed 40.

Since January 1871, there have been only a half-dozen instances, including the present, when the S&P 500’s Shiller P/E topped 30. Following all five previous occurrences, the benchmark index and/or Dow Jones Industrial Average shed between 20% and 89% of their value.

Value may be in the eye of the beholder, but history couldn’t be any clearer that trouble is brewing for the stock market.

Image source: Getty Images.

Widening the lens tells a different tale

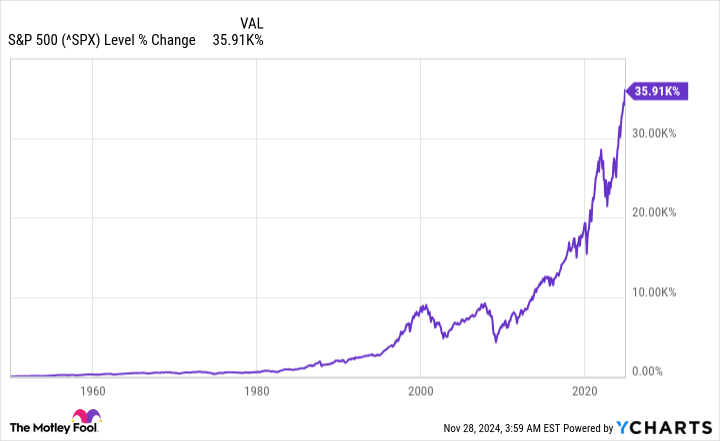

While the near-term outlook for the Dow, S&P 500, and Nasdaq Composite appears dicey, at best, based on a couple of historically flawless valuation metrics, it’s a completely different story if investors lean on history and widen their lens.

A perfect example of time working in investors’ favor can be seen in an analysis conducted by Crestmont Research that’s updated on an annual basis.

The researchers at Crestmont examined the rolling 20-year total returns, including dividends paid, of the S&P 500 dating back to 1900. Even though the S&P didn’t exist until 1923, researchers were able to track the performance of its components in other indexes dating back to the start of the 20th century. Being able to back-test to 1900 resulted in 105 rolling 20-year periods, with end dates ranging from 1919 through 2023.

What Crestmont’s analysis showed is that all 105 rolling 20-year timelines produced a positive total return for investors. In other words, if an investor had, hypothetically, purchased an index fund that mirrored the performance of the S&P 500 at any point since 1900 and held that position for 20 years, their initial investment would have grown.

Furthermore, Crestmont’s data set makes clear that long-term investors weren’t scraping by with menial gains. The annualized average total return for 50 of these 105 rolling 20-year periods topped 9%, which on a compound annual basis would double an investor’s money every eight years.

Even with the stock market breaching never-before-seen valuation thresholds, there’s an extremely high probability that the Dow Jones Industrial Average, S&P 500, and Nasdaq Composite will be markedly higher 20 years from now.

Sean Williams has no position in any of the stocks mentioned. The Motley Fool has no position in any of the stocks mentioned. The Motley Fool has a disclosure policy.