James Mackintosh , The Wall Street Journal 4 min read 13 Mar 2024, 11:32 AM IST

Summary

Artificial intelligence and other sectors are inflated for sure, but to this columnist speculative mania isn’t evident.

When everybody’s talking about a bubble in the stock market, should we worry or relax? The answer from past bubbles seems to be a bit of both—with one big caveat about today’s market.

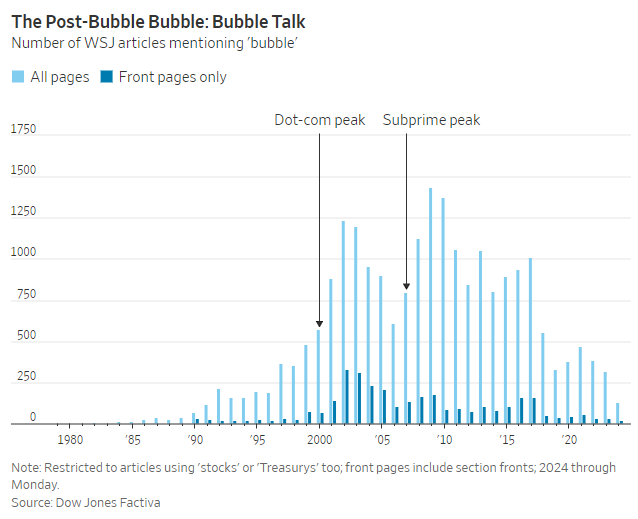

The caveat comes first. While it might feel like everyone in the markets is talking about whether there is a bubble, mentions in the media and searches on Google aren’t especially elevated.

Unfortunately, this was also true before the great dot-com bubble that burst in 2000, the credit bubble that burst in 2007 and—although the data is only for the English language—the China bubble of 2015. In all three cases investors were focused on the bubble, but relatively little was written about them until afterward, when the number of articles and searches exploded as investor portfolios imploded.

This undermines the argument for relaxing, which comes from human nature: If everyone is talking about a bubble, investors ought to be cautious about buying, making it hard for a bubble to inflate.

View Full Image

The trouble with trying to foresee bubbles is twofold. First, before a bubble bursts it is often obvious to those paying close attention, but they can’t get the message out widely enough to take the air out of it. It’s hard for a newspaper to keep warning of a bubble without boring its readers; it’s hard for readers to avoid buying stocks when past warnings have been followed by yet-higher prices. As the old joke has it, a bubble is when other investors are getting rich and you aren’t. When that happens often enough, most investors either stop listening to the warnings or join in despite their misgivings.

Second, when prices keep going up it’s natural to change one’s views. Investors (and journalists) get drawn into the grain of truth from which the bubble inflated, both because it is true and because the huge rise in prices appears to prove the bears wrong. Cassandras are ignored as bubbles inflate, or lose their jobs, as high-profile tech bear Tony “Dr Doom” Dye, chief investment officer of a division of UBS, did in March 2000. The dot-com bubble burst the same month, and the underperforming division became one of the best-performing fund managers in the world that year thanks to the positions it inherited from Dye.

In 1929, Barron’s, our sister publication, was a perfect example of what happens, when it opined: “Although considerable speculation cannot be denied, neither can it be denied that existing prices have developed in spite of years of back-seat fright. Such lasting strength looks more like health than fever.”

When share prices crashed a month later, it turned out the market was very, very sick.

Something similar happened in the dot-com bubble. One example: A front-page piece in The Wall Street Journal in March 2000 hailed the “New Economy” technology stocks as secure against higher interest rates or oil prices while rapidly expanding.

“For all the talk of a high-tech bubble, there is a basic logic driving the divergence of market values: High-tech is where the growth is,” it said.

We now know that the dot-com bubble had started to deflate two weeks before the piece was even published. The Nasdaq dropped almost 80% to its low two years later.

This is uncomfortable reading for today’s market pundits. The “New Era” of 1929 was real. Mass production and motoring had transformed the economy, and productivity had soared. Likewise the “New Economy” of the internet in 1999.

On a smaller scale, legal cannabis, commercial space flights and government support for clean energy were real in 2020-2021 (meme stocks not so much). The problem in a bubble isn’t usually that the story is wrong, but that the price is wrong, because investors are wildly overoptimistic about how fast or how profitable the changes will be. By the time the bubble is fully inflated, investors no longer care about facts at all, merely who the next buyer will be (meme stocks jumped straight to the final stage).

For investors, price is still the question today. I don’t see the scale of speculation that was so obvious in 1929, 1999, China in 2015 or parts of the U.S. in 2020-21. There is also a genuine productivity story to tell about artificial intelligence, even though the scale of efficiency improvements from AI remains a matter of guesswork, given the obvious drawbacks of current systems.

The parallels to the past make me worry that I’m repeating the errors of the past in thinking this isn’t yet a stock bubble, but merely a bit of froth. Certainly investors expect the good times to continue, shown by high valuations—albeit not on the scale of 2000—on top of high profits, as veteran bubble watcher Jeremy Grantham of Boston’s GMO points out. I suspect one or the other will have to give, and if both drop it will hurt. My profession has a terrible record overall in spotting bubbles, but at least this time I can’t see a speculative mania in the overall market.

Write to James Mackintosh at james.mackintosh@wsj.com

Catch all the Business News, Market News, Breaking News Events and Latest News Updates on Live Mint. Download The Mint News App to get Daily Market Updates.