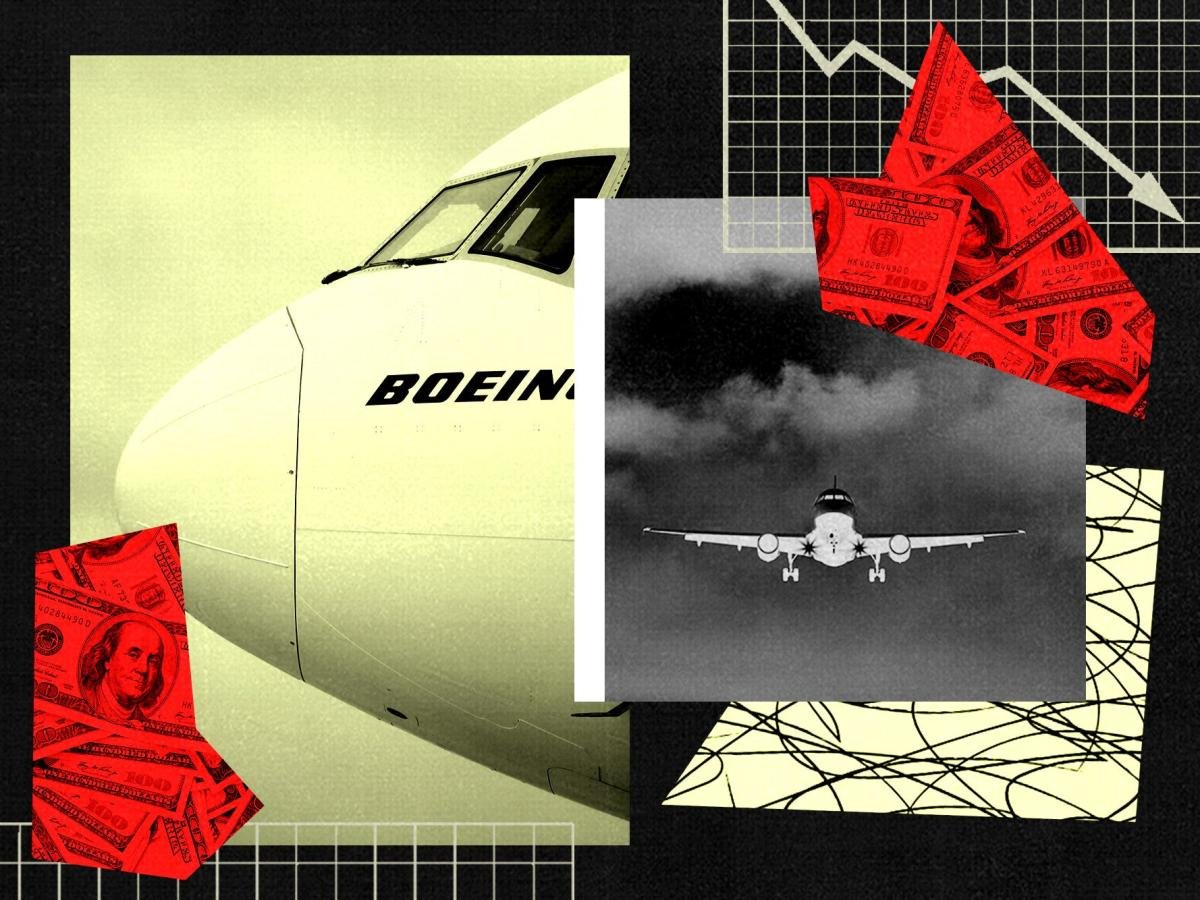

If only Boeing’s problems were just about a nightmare flight — a screw loose, a blown-out door plug, and 177 people who will probably need therapy for the rest of their lives. But as the iconic American plane manufacturer tries to make amends for the disastrous Alaska Airlines flight in January, it’s become clear that Boeing’s problems run far deeper. They expose decades of American corporate philosophy gone awry.

Boeing is a quintessential example of America’s rotting business culture over the past 40 years. The company relentlessly disgorged cash to shareholders when it could’ve spent it on building a better (and safer) product. Investments that could’ve benefited employees, communities, and other corporate stakeholders were often sacrificed at the altar of efficiency and free cash flow. Boeing focused on pleasing Wall Street because that’s how American executives believe companies should operate.

“The people who are at the top are there for a reason, and it’s basically to maximize shareholder value,” the University of Massachusetts economist William Lazonick told me. “It’s so ingrained in their thinking they don’t understand the problem itself. It’s built into the structure of these companies.”Simply changing CEOs or hiring more engineers won’t make Boeing’s problems go away. The company needs to rethink its very reason for existing and what it should provide to society as an enterprise. A good American company isn’t just a vehicle for financial returns; it is first and foremost an employer, a contributor to economic and/or technological innovation, and a source of US power. Whether the recent disasters shake Boeing out of its somnambulance remains unclear. It’s also questionable whether other major companies with a similar maximize-shareholder-value-at-all-costs ethos will learn from the mistakes. But it’s clear that what Boeing — and the entire American corporate body politic — needs is nothing short of a philosophical counterrevolution.

There was a time when pilots had stickers on their bags that said, “If it ain’t Boeing, I ain’t going.” Founded in 1916, the manufacturer helped the US launch NASA and win World War II. For decades it was the pinnacle of American engineering. “Boeing was America’s crown jewel,” William McGee, a journalist, advocate, and aviation-industry old hand, told me. “It was one of the most important and impressive companies in the US.”

This started to change in the late 1980s when T.A. Wilson, the last Boeing CEO with an engineering background, was replaced by Frank Shrontz, an attorney and businessman. The choice was a signal to Wall Street that engineering excesses would be curbed in favor of cost discipline and investor rewards. Lazonick’s research indicates that from 1998 to 2018, Boeing did $61 billion worth of share buybacks to pump its stock price and paid out $29.3 billion in dividends. Over these three decades of plenty for Boeing’s shareholders, the company’s staff was asked to penny-pinch. An investigation into battery fires on Boeing’s 787 Dreamliner in 2013 found that it wasn’t allowing engineers to stress test its products enough, that it wasn’t catching manufacturing defects, and that passengers could be in danger as a result. But he finance guys loved Boeing’s new focus, and the C-suite — which receives the lion’s share of its compensation in stock — loved it too. In the first quarter of 2019, Boeing announced a $2.7 billion stock buyback, and the market rewarded the company with an all-time-high share price of $426.76.

But later that year, it all fell apart.

The 737 Max 8 was supposed to be the most efficient, cost-effective, environmentally friendly narrowbody on the market. Instead, the plane exposed the rot at the core of the company’s culture. In his book “Flying Blind: The 737 Max Tragedy and the Fall of Boeing,” the journalist Peter Robison wrote that when the new model was being built, managers asked for a detailed accounting of every test flight and talked frequently about how any change had to “buy its way onto the airplane.” A manager lamented to one of Robison’s sources that people would “have to die” before Boeing made changes to the aircraft. And so they did: Two crashes — which were the result of the company’s attempt to work around a technical failure — claimed the lives of more than 300 people and grounded the 737 Max 8 for about 20 months. Boeing’s stock cratered, and France’s Airbus, a rival once colloquially known as “Scare Bus,” started to eat the American company’s lunch.

Executives promised to fix the problems that plagued the 737 Max 8, but the recent Alaska Airlines Max 9 mess has returned the focus to Boeing’s communication, supply chain, and overall quality-control failures. In Boeing’s quarterly earnings call at the end of January, President and CEO Dave Calhoun (who was hired after the previous 737 Max disaster) promised more of a focus on quality and encouraged employees to speak up about issues on the factory floor.

“Since day one, we’ve been focused on inculcating safety and quality to everything that we do,” he said, “and getting back to our legacy of getting engineering excellence back at the center of our business.”

To many talking-head Wall Street analysts and TV stock influencers, Calhoun’s comments were enough. Sure, this is a rough period for the company, but Boeing would be fine. Buy the dip. Others in the aviation industry aren’t so sure. United Airlines CEO Scott Kirby, one of Boeing’s customers, called the Max 9 fiasco “the straw that broke the camel’s back.” He expressed frustration at Boeing’s seemingly constant blunders and its nearly five-year delay in the delivery of the Max 10 (which hasn’t been certified by the Federal Aviation Administration). “We’re going to at least build a plan that doesn’t have the Max 10 in it,” he told CNBC.

Rather than a blip on the radar, this should be a come-to-Jesus moment for Boeing — a moment when it puts engineering back at the center of its culture. Some have argued that Boeing’s problems go back further and are bigger than the recent quality issues. But the problems are the result of something even bigger than Boeing.

The transition from an obsession with engineering to an obsession with financial engineering at Boeing, Lazonick told me, wasn’t just the case of one company suddenly changing strategy; it “reflected what was going on in the US.”

Until the 1970s, he says, corporations were generally considered parts of a community with responsibilities to a plethora of stakeholders: the employees who work for them, the communities that house them, the customers who pay for their products.

But then the US stock market flatlined, and the economy was in the doldrums, so Wall Street and Washington decided that the way American companies did business needed a shake-up. This wasn’t a simple tweak around the edges — refining regulations and adding a few new roles to executive teams — it was about an ideological full-court press to change American corporate culture.

At the root of this shake-up was the influence of the economist Milton Friedman of the University of Chicago. In Friedman’s view, humans are selfish and look out for their own interests by nature. He argued that meant a company would see its social responsibility as being to its shareholders and its shareholders alone. One of Friedman’s disciples, the economist Michael Jensen, took the theory a step further in 1976 and argued that the corporation should be built to serve the interests of shareholders. Soon the two economists’ ideas were finding acolytes at business schools, think tanks, and congressional offices around the country.

Jensen in particular pushed for CEOs to be paid in stock, arguing that they were being paid like bureaucrats and needed their compensation to be more in line with performance. This incentivized CEOs to maximize profits for shareholders. It’s probably no surprise that CEO pay increased by 1,322% from 1978 to 2020.

The ideas also started to permeate Washington. Rule changes had allowed companies to repurchase their own shares, a practice that was previously considered stock manipulation and a general waste of capital that should be reinvested in the company. It also opened the door for Wall Street’s corporate raiders to pressure management to buy back stock to juice the price. Money that could have been spent investing in workers or products instead went straight to investors. By the 1990s, nary a thought was given to whether efficiency was enough of a reason to send jobs overseas. There was no time for that while politicians were busy talking about how America should be run as a business.

The CEO who best personified this ideology was Jack Welch, who helmed General Electric from 1981 to 2001. During his tenure, he was celebrated as one of America’s great CEOs for putting shareholder primacy into practice. He sliced costs for the things that had made the company innovative — like research, development, and quality control — and siphoned them off to shareholders in the form of buybacks and dividend payments. Wall Street rewarded his mentality richly, GE’s stock peaked at $318.26 in 2000, and Welch’s disciples at GE spread out all over corporate America. But a corporation can run on past innovation only for so long. In 2018, after over 100 years of prestige, GE was dropped from the Dow Jones Industrial Average because of the work Welch did to hollow it out. During the first few years of his tenure he fired a quarter of the company and continued to fire 10% of the workforce annually thereafter. He was such a fan of sending factories abroad — to American unions’ ire — that he infamously said, ”Ideally, you’d have every plant you own on a barge.” GE was stripped to free up cash for shareholders time and time again — one of those, of course, being Welch. Even after he left the company, his pay package was so avaricious that the Securities and Exchange Commission fined GE in 2004 for failing to disclose its magnitude. The problem with playing Wall Street’s game is that you have to keep playing forever, and the efficiency doctrine has diminishing returns.

“The ones where the most value is being extracted are the ones that were the most innovative in the past,” Lazonick told me, “but then they go into decline.”

An entire generation of politicians and executives preached the doctrine of efficiency in the name of maximizing profits for shareholders, and we’ve seen the results: stagnant wages, massive inequality, legislators captured by industry lobbyists, and companies that coast on past innovation and financialization because it’s easier than investing in something new.

As Boeing has been forced to reckon with the corporate culture it developed over the past 40 years, corporate America has been forced to face the long-term cost of its obsession with shareholder primacy and efficiency. We’ve lost a sense of balancing stakeholder interests. Not every company is as rich as, for example, Meta, which has been able to invest $50 billion in Reality Labs (the “metaverse”) since 2020 and still buy back its own stock at its highs. Meanwhile, Deutsche Bank has projected that across the S&P 500 buybacks will surge to $1 trillion in 2024. Surely not all of these companies occupy the same reality — virtual, financial, or otherwise. Besides, part of Wall Street’s good vibes for Meta stem from the fact that the company has cut 22% of its workforce over the past year. In an economy where taxpayers kept some businesses afloat through the pandemic, widespread layoffs in the name of efficiency and shareholder value will hit a nerve that has been irritated for years now.

Americans — whether they’re shareholders are not — have started to notice their contributions to the corporations as workers and taxpayers are being taken for granted, and they’re naturally angry. The populism that has taken over our political discourse is anger over inequality harnessed for political action. In response, executives have offered only lip service. In 2019, the Business Roundtable, an advocacy group formed in the 1970s for corporations, read the populist tea leaves and published a statement that said the purpose of a corporation was to serve all stakeholders, “customers, employees, suppliers, communities and shareholders.”

The problem is it’s hard to see how corporate behavior has actually changed since then. Look at General Motors. Right now, the company is trying to keep up in a global race to electrify the car industry. If there was any time to focus on productive investments over shareholders’ wallets, this would be it. When the United Auto Workers union went on strike in September, CEO Mary Barra warned workers that it would cost the company money that should be invested in that transition. But in November, after the strike, she announced a $10 billion stock buyback, the company’s largest share-repurchase plan and a larger sum than it gave its workers. The size of the buybacks is even more staggering when you consider that the company promised to spend $35 billion total on developing EVs from 2020 to 2025.

Companies like GM and Boeing are crucial to the American economy. Their success keeps people employed and enriches communities, which is good for society. Maintaining and growing these iconic companies is a long-term business, but the people who run the business are motivated to play a short-term game.

“Boeing is vital, but we don’t treat it like it’s vital,” McGee said. “We treat it like a casino.”

There are ways to change all of this, as Lazonick outlines in his 2023 book “Investing in Innovation.” Companies could decouple executive pay from stock prices or change the composition of boards to include employees. But more fundamentally, it will take a total rethink of America’s corporate incentive structure. Instead of favoring shareholders and playing a quarterly game with Wall Street, C-suites should prioritize sustainable, long-term businesses that employ as many productive workers as possible. This means companies won’t suddenly fall out of the sky when the economy sours or their products start to give way for lack of investment.

In Boeing’s case, that could mean bringing suppliers closer to home, investing in more layers of quality control, and allowing more time for testing and research. It could mean a more expensive, more redundant company, but a better one. The first step is believing that the state of Boeing is not a natural one — that it can be changed with conscious effort. We just have to choose a better way.

Linette Lopez is a senior correspondent at Business Insider.

Read the original article on Business Insider