Jon Sindreu , The Wall Street Journal 3 min read 27 Mar 2025, 08:19 PM IST

Summary

Though the trade war has heightened uncertainty, slower earnings growth and a cooler labor market would likely have impacted the market regardless.

With the S&P 500 having suffered a correction and the word “recession” being uttered across Wall Street, it is tempting to link the fate of the stock market to the Trump trade war. But investors shouldn’t forget that danger can come from many directions.

Equities have been in wait-and-see mode this week: The S&P 500 first rose on the back of reports that tariffs scheduled for April 2 may be more targeted than initially suggested, but tumbled Wednesday amid news that automakers won’t fully manage to escape import duties.

Many economists, including those at the Federal Reserve, have cited tariffs as a reason to trim growth forecasts. Cuts in the federal workforce and lower immigration could further weigh on spending. Shares in the S&P 500 consumer-discretionary sector, which includes car manufacturers and specialty retailers, are down 11% this year.

View Full Image

Overall, it seems clear that hopes of a return to more orthodox policymaking have become the main reason to buy the dip. Attributing all of the market’s stumbles to President Trump, however, is a risky simplification.

Looking ahead to first-quarter results, which corporations will start reporting in a couple of weeks, the S&P 500’s earnings-per-share are expected to grow 7.1% from a year earlier, according to FactSet. This might seem decent after seven straight quarters of expansion, but the level of expected earnings is now 4% lower than analysts had forecast at the end of last year—a larger-than-average reduction.

All 11 S&P 500 sectors appear to be doing worse than previously believed, and earnings growth is decelerating in nine. American Airlines, footwear maker Nike and package-handling giant FedEx are among the latest companies to trim their business outlooks.

Part of this has been blamed on tariffs, perhaps rightly so. Even though first-quarter earnings and even more forward-looking forecasts don’t reflect their full impact yet, uncertainty is hurting business and consumer confidence.

View Full Image

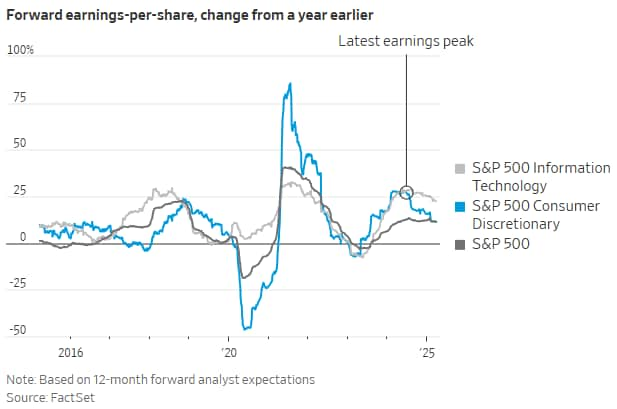

But earnings-per-share growth among consumer-discretionary firms started rolling over before the U.S. election, in the summer of 2024. For hotels and restaurants, it happened almost a year earlier. The woes of the industrial economy aren’t new either: FedEx, which is a bellwether for supply-chain logistics, has been repeatedly lowering its guidance since 2023.

Another smoking gun is technology, the second worst-performing sector this year: Its profit growth also peaked in 2024, based on forward 12-month earnings.

Much of the equity correction may just be a reassessment of steep tech valuations. In February, the “Magnificent Seven”—Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Nvidia, Tesla, and Meta—traded at nearly 45 times forward earnings despite reasonable concerns over China’s artificial-intelligence rise. Now, their price-to-earnings ratio is 35, having collectively lost 11.3%.

These companies’ huge presence in the headline market-cap weighted index is a big reason why it has declined 2.9% this year, while remaining flat in equal-weighted terms. Further backing this view, the Cboe Volatility Index, or Vix, which investors use as a “fear gauge,” has only increased moderately.

Profit cycles often turn without causing recessions, and this could be the case today. If so, delving back into equities makes sense: For time horizons beyond two years, the cheaper valuations that accompany a profit deceleration tend to compensate investors for lower initial returns.

View Full Image

Of course, a correction can become a bear market—an equity drawdown of 20% or more—even without a recession. Monthly data by economist Robert Shiller going back to 1871 shows that this has happened on three occasions: The “Kennedy Slide” of 1962, the chaos that followed the Black Monday flash crash of 1987 and, more recently, the monetary tightening of 2022, which also involved inflated tech valuations. Yet, following all of them, stocks rebounded promptly.

The real worry is that 54% of corrections did precede recessions, in which case the drag on returns was long-lasting.

So far, weak data has mostly been confined to “soft” sentiment surveys like the Conference Board’s, which on Tuesday showed forward-looking expectations for income, business, and labor-market conditions hitting a 12-year low. More reliable official indicators have been robust or quickly reversed: January’s poor retail-sales figures were followed by a February jump.

Nevertheless, the hot postpandemic economy is over and has been cooling for months. Once-unrelenting consumers have turned budget-conscious, high mortgage rates are restricting home-building and job-market trends point to less hours worked and cyclical industries hiring less. Not unlike in the equity market, the upside for the broader economy has long been related to the wave of capital spending unleashed by AI-focused corporations. But their appetite to keep it going at lower levels of profitability and valuation remains untested.

Yes, tariffs and budget cuts up the chances of an eventual recession. It doesn’t mean their absence would eliminate it altogether.

Write to Jon Sindreu at jon.sindreu@wsj.com

Catch all the Business News, Market News, Breaking News Events and Latest News Updates on Live Mint. Download The Mint News App to get Daily Market Updates.